Anatomy of the Shoulder

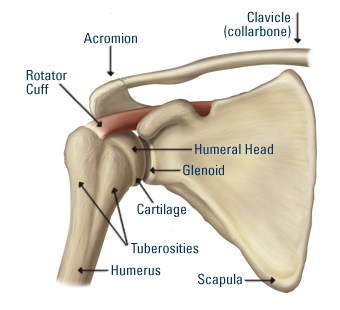

The shoulder joint is the most commonly dislocated joint in the body due to its high mobility which sacrafices its stability (Magee, 2008). The relationship between the top of the arm bone (head of the humerus) and the shoulder socket (glenoid fossa) has often been compared to a seal balancing a beach ball on its nose (Brukner & Khan, 2007). The shoulder joint is therefore very reliant on other structures to maintain its alignment both at rest and during activities (Novotny et al,1998). The video below provides a brief summary of the anatomy of the shoulder.

The shoulder complex is comprised of four joints which contribute to the movement of the arm:

| Video: Anatomy of the shoulder |

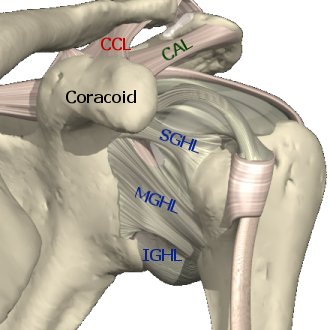

Shoulder Stabilisers (Novotny et al,1998): The shoulder joint is stabilised by the labrum which deepens the socket and increases the surface area of the joint. The front of the shoulder joint is surrounded by the anterior glenohumeral ligaments (figure below). These structures provide stability and resistance to excessive forward motion of the humeral head (figure right). Its function is an important component in preventing recurrent anterior (forward) shoulder dislocations.

|  |

| The anterior region of the joint capsule is supported by superior (SGHL), middle (MGHL) and inferior (IGHL) glenohumeral ligaments (figure left). The anterior glenohumeral ligaments are damaged in 95% of shoulder dislocations (Rowe et al, 1984). Without early treatment repeated dislocation may occur. |

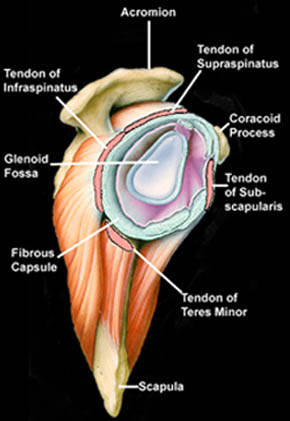

The rotator cuff is a group of muscles that hold the ball at the end of the arm bone into the shoulder socket. The muscles of the rotator cuff are:

This rotator cuff provides stability and enables every day movements of the arm. Other surrounding muscles also contribute to shoulder stability but to a lesser extent. |  Side on view of the shoulder with arm removed |